A few weeks ago, a friend told me about a visit he’d made to the Scottish Parliament at Holyrood to view First Minister’s Questions. He described how Nicola Sturgeon strode in confidently, flanked by her aides, every inch the leader. To start with, she dominated the assembly as she confidently answered the early questions. However, when she was asked questions about the performance of Scotland’s schools and hospitals by MSPs from the Scottish Labour and Scottish Conservative parties, she visibly diminished in stature as she struggled to defend her domestic performance. This got us talking about the extent to which her demands for independence are to distract voters from poor performance on domestic issues. In a wider context, it is a tried and tested political tactic to distract voters from poor performance on domestic issues by hardening the rhetoric on external issues. This is a tactic that Vladimir Putin is keen on and one that we are seeing now with Donald Trump’s new-found, aggressive enthusiasm for dabbling in international affairs, after several failures with home affairs.

At the risk of falling into the trap of trying to show awareness of a potentially damaging misunderstanding by attempting to rule it out, let me make it clear that I am not equating Nicola Sturgeon with either Vladimir Putin or Donald Trump. However, considering the differences between Nicola Sturgeon and Vladimir Putin in parallel does illustrate the first point that I want to make in this post: the reciprocal link between authoritarianism and dogma. For the sake of clarity, here are some definitions of these words that reflect the way in which I use them:

authoritarian: favouring or enforcing strict obedience to authority at the expense of personal freedom

dogma: a principle or set of principles laid down by an authority as undeniably true (literally “that which one thinks is true”).

dogmatic: inclined to lay down principles as undeniably true.

In my view – one that is probably not too controversial – Vladimir Putin is someone who is firmly embedded in an authoritarian way of operating. As a result of this, he acts dogmatically: laying down principles as an authority that expects obedience and does not expect anyone to deny the truth of them. Being authoritarian leads, therefore, to being dogmatic, but I think the converse is also true: being dogmatic leads to being authoritarian. In fact, this may well be how people get to being authoritarian in the first place. This does not usually happen consciously, therefore will tend to be denied. This is the point at which I want to think about Nicola Sturgeon, but before I do I just want to make one further point about dogma. Dogma can be a principle that we just take on board from an authority without questioning too much (probably how dogma is most commonly thought of). It is also entirely possible for principles that we have come to believe for ourselves after careful consideration to become dogma. This can happen over time if we stop questioning those principles and as a result start to treat them as undeniably true. In some ways, the latter type of dogma is more dangerous than the former because you are more likely to think that you are not being dogmatic.

Returning to Nicola Sturgeon, I wouldn’t say that she is someone embedded in an authoritarian way of operating, but I would say that she is dogmatic about Scottish independence. The trouble with dogma is that if we believe in a principle, for example independence for Scotland, strongly enough that we think it to be undeniably true then it will naturally seem like it is the best thing for other people too. We might then be tempted to go beyond simply arguing for what we believe in and attempt to manipulate people into supporting us, for example by putting forward arguments that knowingly present less than the whole truth or by timing decisions around factors that benefit our cause. We are now seeking to impose our will. We are acting in an authoritarian manner. We also risk blinding ourselves to counter arguments. In arguing for an independence referendum before the UK leaves the EU, Nicola Sturgeon is behaving in an authoritarian manner because she is seeking to have the vote at a time when she thinks she has the greatest chance of winning, when she thinks people will be most disenchanted with the UK, when they are likely to be most scared about the reality of Brexit. She also presents less than the whole truth in what she says about Scotland’s future being as an independent member state of the EU. She has no idea whether that is possible. However, she also appears to have blinded herself to the fact that if she were to lose a referendum on her timescale then Scotland would remain part of a UK that has been saddled with a less good outcome from Brexit than it might have had because of the distraction caused by the referendum campaign.

So, I have argued that authoritarianism and dogma are linked in a reciprocal relationship. You may have picked up from my language that I don’t think either of them are a good thing. What, therefore, are the balancing forces in politics? Liberalism is the balancing force to authoritarianism and, just as authoritarianism is reciprocally linked with dogma, liberalism is reciprocally linked with scepticism. Once again, here are some definitions of these words that reflect the way in which I use them:

liberal: willing to respect or accept behaviour or opinions different from one’s own; open to new ideas

sceptic: a person inclined to question or doubt accepted opinions

Why is it that I think liberalism and scepticism are linked? The inclination to question or doubt your own opinions opens the door to respecting or even accepting other people’s opinions. Conversely, the best way to show respect for another person’s opinions is to question those opinions (whether out loud or in your own head), rather than dismissing, ignoring or insulting them.

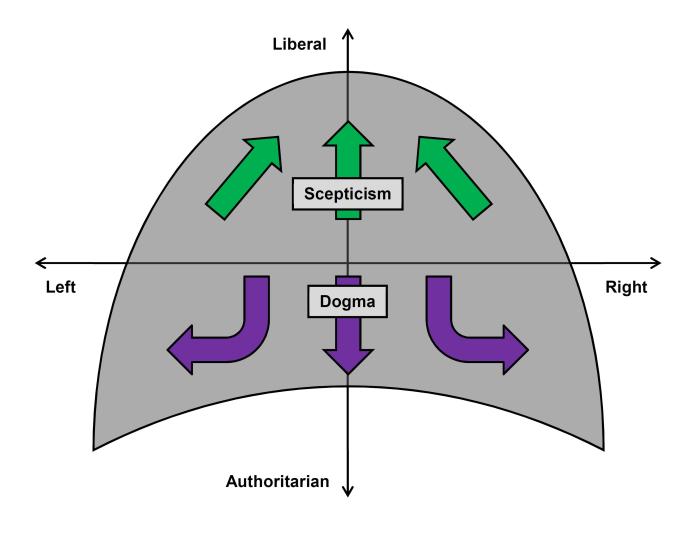

Politics is often talked about in terms of a one dimensional spectrum, with left (or progressive) and right (or conservative) as opposing forces. In this view of politics, communism is at the extreme left, fascism is at the extreme right and liberals are generally viewed as being somewhere in the middle. This model doesn’t work for me, mainly because centrist politicians are as prone as those of the left or the right to being dogmatic therefore authoritarian about their views and cannot, therefore, necessarily be described as liberal. Here is the best way I can find of representing my view of politics in a two-dimensional diagram, with the opposing forces of liberalism and authoritarianism forming the second dimension:

The enclosed, grey area crudely represents the region in which politics operates. I have already described how scepticism pushes us towards liberalism and dogma pushes us towards authoritarianism. Whilst such dogmatic authoritarianism can push us to more extreme left or right wing view, note that there is also a purple arrow going straight down. This represents what I mentioned above about it being perfectly possible to maintain centrist views, but in a dogmatic (and therefore authoritarian) manner. This is, I believe, where the politics of the centre often goes wrong. There is a prevalent belief that simply being in the centre, neither too far to the left nor too far to the right, means being liberal. This is not true. Being liberal is about the way in which you do politics. You can be a liberal in a right-wing party or a liberal in a left-wing party or even, although not necessarily, a liberal in a party which is called liberal. I believe that sceptical liberalism will pull you away from the extremes of left and right, but with significant flexibility to manoeuvre to the left and to the right to find the best solutions for the situation at the time you are looking and the policy area you are looking at. On the other hand, being in the centre probably protects you from the worst excesses of authoritarianism (totalitarianism – the pointy bits at the bottom left and right of the grey area) which probably only occur in far left and far right politics.

The enclosed, grey area crudely represents the region in which politics operates. I have already described how scepticism pushes us towards liberalism and dogma pushes us towards authoritarianism. Whilst such dogmatic authoritarianism can push us to more extreme left or right wing view, note that there is also a purple arrow going straight down. This represents what I mentioned above about it being perfectly possible to maintain centrist views, but in a dogmatic (and therefore authoritarian) manner. This is, I believe, where the politics of the centre often goes wrong. There is a prevalent belief that simply being in the centre, neither too far to the left nor too far to the right, means being liberal. This is not true. Being liberal is about the way in which you do politics. You can be a liberal in a right-wing party or a liberal in a left-wing party or even, although not necessarily, a liberal in a party which is called liberal. I believe that sceptical liberalism will pull you away from the extremes of left and right, but with significant flexibility to manoeuvre to the left and to the right to find the best solutions for the situation at the time you are looking and the policy area you are looking at. On the other hand, being in the centre probably protects you from the worst excesses of authoritarianism (totalitarianism – the pointy bits at the bottom left and right of the grey area) which probably only occur in far left and far right politics.

In a previous post I shared some thoughts on what truth might be and how we might go about finding it. I suggested that in order to move closer to the truth we need to:

- have a current position

- accept that our current position may not yet be the truth of the situation

- understand alternative positions.

Thinking about it, being a sceptical liberal is the key to the search for truth that I described. Scepticism is vital to accepting that our current position may not yet be the truth of the situation. Having that liberal respect for other people’s positions is vital to understanding alternative positions. I have mentioned before that I am inclined to scepticism. I call myself both a liberal and a sceptic.