“The mere fact that they [political parties] exist today is not in itself a sufficient reason for us to preserve them.”

Following the resignations of several MPs from the Labour and Conservative parties back in February, I reviewed some of my writings on political parties. They started by my questioning the role of truth in our politics with some thoughts on the way politicians try to win our votes by feeding our desire for certainty about the future, when this is something that no one can offer with any degree of honesty (Post-Truth Certainty). However, it was during the 2017 General Election campaign that I started to seriously question the role of political parties and the manners in which they corrupt our system of representative democracy (A New Kind of Politics?) which then lead me to conclude that the only honest vote was a vote for a person, not for a party (Vote Person, Not Party). After the election dust had settled, I went on to consider the lies and bribery inherent in that driving force of political parties: the manifesto (Manifestos: The Longest Bribery Notes in History).

Following the resignations of several MPs from the Labour and Conservative parties back in February, I reviewed some of my writings on political parties. They started by my questioning the role of truth in our politics with some thoughts on the way politicians try to win our votes by feeding our desire for certainty about the future, when this is something that no one can offer with any degree of honesty (Post-Truth Certainty). However, it was during the 2017 General Election campaign that I started to seriously question the role of political parties and the manners in which they corrupt our system of representative democracy (A New Kind of Politics?) which then lead me to conclude that the only honest vote was a vote for a person, not for a party (Vote Person, Not Party). After the election dust had settled, I went on to consider the lies and bribery inherent in that driving force of political parties: the manifesto (Manifestos: The Longest Bribery Notes in History).

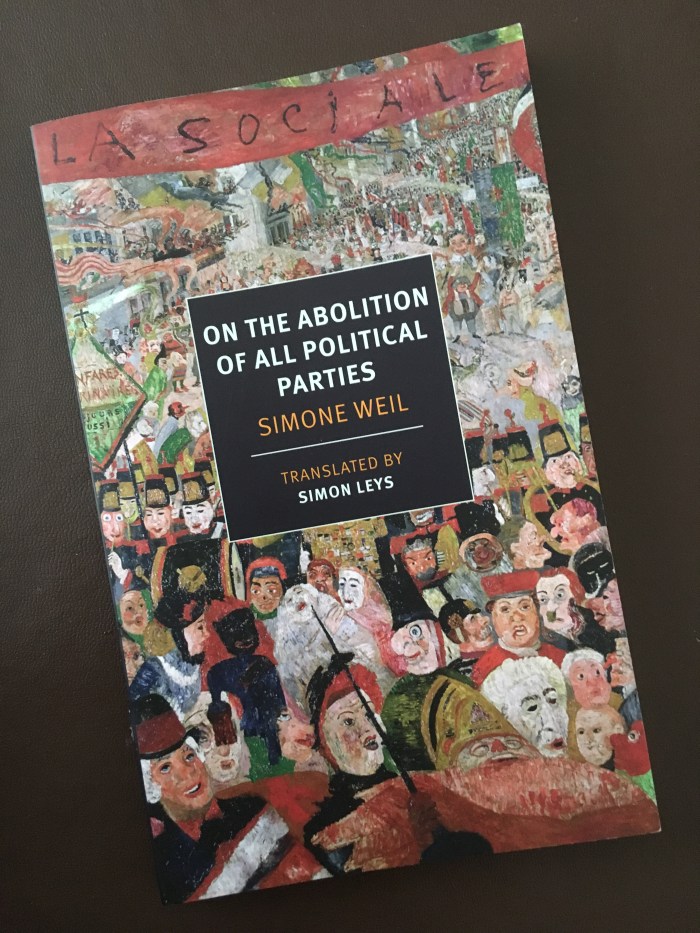

Having re-read these articles, it occurred to me that I should redress the balance by studying something of the history of political parties or some form of justification for their existence. In searching a couple of internet bookstores, however, I stumbled across the slender volume about which I am writing now. Not being widely read in philosophy, I had never heard of Simone Weil but found the story of her short life very interesting. Discovering that a French thinker, born 65 years before me, had, in wartime writing that sprung out of reimaging France for a hoped for post-occupation future, reached apparently similar conclusions to the ones I had about the pitfalls of political parties was both fascinating and emboldening.

The opening paragraph of her work immediately shook me out of any complacency with its assertion that her conclusion only applied to Continental political parties in their plebeian origin and not the English political parties of aristocratic origin. With some thought, however, I realised that when she was writing in 1943 the Labour party had yet to form a majority government of the UK. I can’t say how much our politics has changed since 1943, or whether any such change has been driven by a party that emerged more from the people than the aristocracy, but I find that all her descriptions of the ills of political parties resonate strongly with the politics I observe in early 21st century Britain.

Weil argues that political parties become ends in themselves, when our only end should be goodness, which can be understood as truth and justice. How often do we hear the phrase “for the good of the party” (usually measured by votes or financial donations)? That’s when the party has become the ends. There is currently a corruption story rumbling on in Canada in which “The former Attorney General says Trudeau and his staff spent months trying to convince her that taking the company to trial would cost Canadians jobs, and their party votes.” (Trudeau and Wilson-Raybould: The scandal that could unseat Canada’s PM, BBC News, 28th February 2019). The party had become the ends. Our ends should only ever be truth and justice and we should demand this of our elected representatives too.

There is so much more to draw out from this work about the evils of political parties but, rather than labouring the point further (when anyone who is interested can just read the book for themselves), I want to offer some thoughts on Brexit referenda that came to me whilst I was reading it. After all, the weaknesses of our political parties have resulted in the European question being left to fester until such time as it is very difficult to resolve it in any practical manner. They also make it virtually impossible for the parties to resolve the crisis they have allowed to evolve.

Firstly, in taking a step back to lay the groundwork for her argument, Weil summarises Rousseau’s notion of the general will. In order for the general will to be superior (as measured by truth and justice) to any individual wills the most important condition that must be met is that “at the time when the people become aware of their own intention and express it, there must not exist any form of collective passion”. To put it another way “When we are calm it is easier to make sensible choices” (Calm). Just pause and reflect on the 2016 referendum. Both sides strove to generate fear, whether of immigrants or of financial meltdown. It was all about winning and losing: words that generate huge levels of passion (Winning and Losing: A Very Brexit Problem). It seems fair, therefore, to argue that the referendum cannot have determined the general will. However, unless a second referendum was to be carried out in a vastly different manner it would similarly fail to determine the general will, regardless of whether or not it reversed the decision of the first.

Secondly, Weil finishes her essay by pointing out that we have learned from politics to approach complex problems in entirely the wrong manner. We take sides, for or against, and then try to justify our position. This avoids thinking altogether. The only path to truth is to meditate upon the problem and then express the ideas that come to our mind. In order to do this we first need to listen carefully and respectfully to a range of opinions on the problem, in other words to be liberal (Sceptical Liberalism vs Dogmatic Authoritarianism: The Second Dimension of Politics). Only then will we be ready to ponder patiently in search of the truth (Christmas 2017: Pondering Perplexities).

Returning to the main theme of the book, I note that the newly formed “Independent Group” of MPs is in a rush to become a political party (Independent Group’s plans to register as Change UK party angers petitions site, The Guardian, 29th March 2019). They know no other way. In my exploration of the Bible, I am currently reading 1 Samuel in which, after the chaos described in Judges, God accedes to the Israelites’ demands and lets them have a king to rule over them. It is clear that God regards this as a rejection by his people of Himself as ruler. Yet Judges is also clear that the moral chaos was because there was no king. They couldn’t cope having God – having truth and justice – as their sole end. Although I strongly dislike the phrase, perhaps having a king was ‘a necessary evil’. Perhaps political parties are such a necessary evil for us. Even if that is true, this book should be required reading for anyone with even a passing interest in politics in order to remind ourselves of the nature of the evil that is deemed necessary.

I’ll finish these reflections, as I started, with a quote from the text:

“Political parties are a marvellous mechanism which, on the national scale, ensures that not a single mind can attend to the effort of perceiving, in public affairs what is good, what is just, what is true.”