Avid readers of my Facebook timeline will no doubt recall a seminal post that I made on 28th February of this year:

Cycling home from work just now, I was reflecting on the virtues of my mode of transport. In addition to the health benefits (both physical and, more importantly for me, mental), by breathing in all the particulate emissions being belched out by the vehicles I was sharing the A432 with I was helping to clean the air for everyone else. However, it then occurred to me that I must be breathing out more carbon dioxide than I would be from a sedentary driving position in my car. Now, hopefully the increase in my personal CO2 emission was considerably less than that which my car would have emitted if I’d chosen to drive, but this did get me thinking about the CO2 emitted by people. To what extent does the vast population of people on the planet contribute to climate change simply by means of their respiration? It’s not just the numbers being born but, given the massive increases in life expectancy in recent years, the emissions over a life-time. Are there any data on this? When the Youth Climate Protests were happening a couple of weeks ago, I found myself irreverently wondering whether the best thing our generation could have done to preserve the environment for the next generation would have been to have given birth to fewer of them. Maybe there was something in this thought after all…

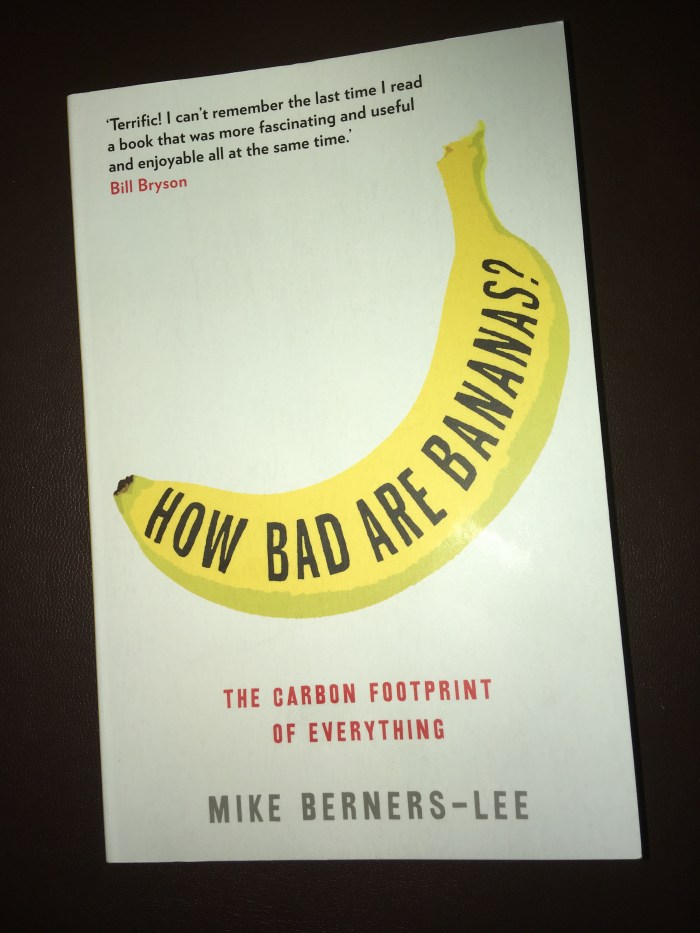

Inspired more by the Youth Climate Protests than my own random ramblings, a couple of weeks ago I ordered two books by climate expert Mike Berners-Lee (brother of Tim): “There’s No Planet B: A Handbook for the Make or Break Years” and “How Bad Are Bananas: The Carbon Footprint of Everything”.

I haven’t actually read these yet but found myself flicking through the latter earlier on today whilst trying to avoid a household task. To my surprise and delight, there was a section relevant to my earlier musings. It turns out that the relative benefits, as far as carbon footprint goes depends on the fuel the cyclist uses:

“If your cycling calories come from cheeseburgers, the emissions per mile are about the same as two people driving an efficient car.”

Carbon emissions are much worse if the cyclist fuels themselves with air-freighted asparagus. However, given a more sensible diet things look much better:

“Is cycling a carbon-friendly thing to do? Emphatically yes! Powered by biscuits, bananas or breakfast cereal, the bike is nearly 10 times more carbon efficient than the most efficient of petrol cars.”

As I found myself doing, the author then drifts onto the carbon inefficiency of living:

“Cycling also keeps you healthy, provided you don’t end up under a bus. (Strictly speaking, dying could be classed as a carbon-friendly thing to do but needing an operation couldn’t.)”

What more does the carbon-conscious cyclist need to know than that? Having since flicked through a few more pages, this book certainly appears to be both highly informative and highly amusing for the carbon-conscious, whether they are cyclists or not.