[A crowded street in Bristol.]

Homeless Lady: Can you spare any change?

Me (awkwardly glancing towards her feet, mumbling): Sorry, no.

Homeless Lady (warmly): Thank you for acknowledging me sir.

[A crowded street in Bristol.]

Homeless Lady: Can you spare any change?

Me (awkwardly glancing towards her feet, mumbling): Sorry, no.

Homeless Lady (warmly): Thank you for acknowledging me sir.

I missed most of the live coverage of Harry and Meghan’s wedding because at the time I was trailing around local charity shops, trying to put together a child’s Anglo-Saxon costume for a school dressing-up day. I wasn’t too disappointed: I’ve never exactly been a ardent royalist. However, as I get older I find myself more inclined to stick with this seemingly anachronistic method of choosing our head of state. Firstly, once you start unpicking one part of the way that the state works the whole thing may end up unraveling: imagine Brexit, but magnified to untangling centuries of constitutional evolution. Secondly, I don’t much fancy any of the alternatives. Let’s face it, electing your head of state doesn’t always end well.

It didn’t take long, however, for me to notice that Bishop Michael Curry’s address had become something of a talking-point. A week later, therefore, I decided to watch it. By that time, I had already read a transcript of the address. In print, I couldn’t quite see what the fuss was about. Don’t get me wrong: I loved the content. It’s just that hearing it in my head in the sort of steady English delivery I’m used to hearing sermons or homilies delivered in, it seemed like something I could have heard at any church service I’ve ever attended. Watching it in full, however, delivered in a style not only at odds with the formality of the surroundings and occasion but also my own expectations of preaching, rendered it many times more powerful. And yet, the passion displayed by Bishop Curry – the effervescent wonder, joy and excitement – are not alien to my experience of faith. They are what I feel deep inside me when I read God’s word and when I hear a preacher bring to life some new aspect of the gospel that I have never considered before. It’s just that, being very English, I don’t show it on the surface. I’m all too careful to be very measured when I speak or, indeed, when I write. It shouldn’t be a surprise if people reacted awkwardly. The style of delivery made it difficult for people to avoid engaging with what was being said and the gospel should always be a challenge to the rich and powerful. But all of us face times in our lives when we have power over others or have to decide how to use our riches, if not financial then perhaps riches of talents or of compassion.

Although I had only put on the Royal Wedding footage to watch Bishop Curry, in the end I found myself viewing the whole service and was much more enchanted by it than I expected. In particular, as the couple exchanged their marriage vows I reflected on my own marriage vows. Although we had prepared for marriage and so the vows weren’t something I made lightly, I found myself thinking about how much better I understand those vows for having lived them for over twenty years. With their emphasis on total commitment, marriage vows provide a welcome antidote to a world that likes to tell us that by asserting individual rights over everything we can predict and control the future. The total commitment of marriage gives us strength to face the future in the knowledge that we do not know whether it will bring sickness or health, riches or poverty. Such commitment is an act of faith, made in the hope that, although we can’t be certain what the future holds, we can be certain that it will be easier if we face it together. That’s something that is worth pooling our individual rights for. It occurs to me that perhaps the point of monarchy is reflected in all this: a mutual commitment made for life to face the uncertainty of the future together. Perhaps this is, after all, better than choosing someone who we can’t completely trust, who offers us a post-truth certainty, with a get out clause that allows us to throw in the towel after four or five years when the going gets tough. That’s no commitment at all.

One day, sometime last year, I was walking across College Green in Bristol and observed a handful of people protesting in favour of repealing the Eighth Amendment of the Constitution of the Republic of Ireland which states:

“The State acknowledges the right to life of the unborn and, with due regard to the equal right to life of the mother, guarantees in its laws to respect, and, as far as practicable, by its laws to defend and vindicate that right.”

My eyes were drawn to one of the banners which read, “Hands off my ovaries”. “Why,” I wondered to myself, “would you go to all the effort of setting up a street protest and then display a banner advertising a total lack of understanding of the issue?” Firstly, the only way I know of to control ovaries is for their owner to choose to take the contraceptive pill, which then may or may not inhibit ovulation. Secondly, abortion is not about intervening with ovulation, but about intervening at a point in time after the ovaries have done their work.

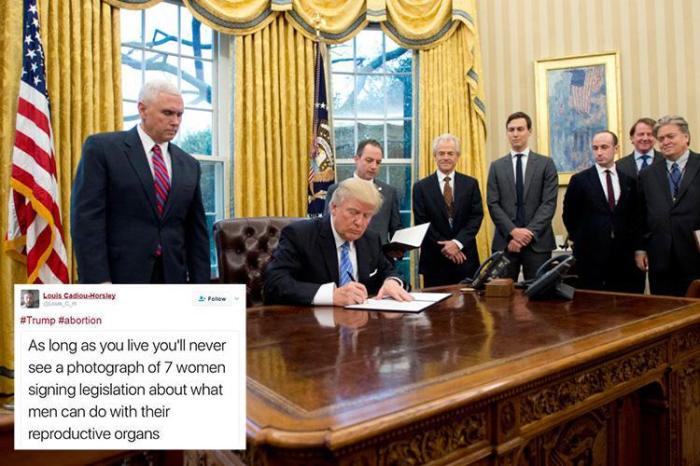

A similar level of misunderstanding was to be observed back in January 2017, when the newly inaugurated Donald Trump signed an executive order reinstating the Mexico City policy, which declares that organisations in receipt of US Federal funds “neither perform nor actively promote abortion as a method of family planning in other nations”. In particular, I remember the following picture being prevalent on Facebook:

Consider the caption. Firstly, only one man signed the order, not seven as stated (or even eight as pictured). Secondly, abortion is not about what women choose to do with their reproductive organs, but about what is chosen to be done to a new body growing inside those reproductive organs. The puzzling thing about all this confusion is that the nouns we use for the process (abortion or termination) are based on verbs whose meaning is quite clear:

abort: to cause to cease or end at an early or premature stage

terminate: to bring to an end; put an end to

An abortion or termination is, therefore, the act of ending a process that has already started; the process of growing a new human body inside a woman’s reproductive organs; the process called pregnancy.

The muddled campaign slogans I have observed are a result of the misinformation that stems from abortion being such a divisive issue. As divisive issues tend to do, it divides people. Once people are divided into two camps, true debate rarely seems to take place. Each camp ends up talking to their own members in language that alienates the other side. As a result, it is all too easy for them to never listen to what the other side is actually saying but only to hear them disagreeing with their own views. So pro-life activists only hear pro-choice activists denying an unborn child’s right to life and pro-choice activists only hear pro-life activists denying a woman’s right to choose. Indeed, pro-choice group Abortion Rights deliberately refers to pro-life groups as “anti-choice”. Similarly, pro-life group SPUC refers to “a radical anti-life agenda”. This makes progress impossible and leaves the many people in the middle struggling to make up their minds. How can you make a decision, with such lasting consequences, when all you can hear are contradictions? What are you supposed to think if you believe that life is precious and that people should have a choice about what happens to their bodies? Surely in the liberal society we are supposed to live in we should be able to talk about life and choice together?

“My Body, My Choice” – the slogan of choice for Abortion Rights – is an argument that resonates strongly, perhaps now (post-Weinstein and Me Too) more than ever. Of course women should have the right to choose what happens to their bodies. All people should have the right to choose what happens to their bodies. For too long, too many women have not had this control, whether through sexual violence or through the demands and expectations placed upon them by a patriarchal society. We should be horrified when any person is physically forced or manipulated by abuse of power into doing something unwillingly with their bodies. Of course no woman should be forced to have a baby. No person should be forced to have a baby. The responsibilities that come with having a baby are life-long and life-changing. Although the physical wonders and demands of pregnancy cannot be shared, the responsibilities that come with it can and should be shared. One of the most distressing implications I see in many pro-choice arguments is that pregnancy is the responsibility of the woman alone. In the sense I have outlined above, I am definitely pro-choice.

In order to talk about a right to life, as enshrined in Article 3 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, it is crucial to first think about when life actually begins. Up to this point, I have carefully talked about pregnancy as being a process of growing a new human body inside a woman’s reproductive organs. Is that body alive? Although this question is crucial, it is not necessarily straightforward to answer. As a starting point, I hope that most readers would agree that the right to life certainly applies from the moment of birth until the moment of death. This is despite the fact that we are constantly changing throughout our lives. Although we may stop growing physically after 15-20 years, we never stop changing physically. In other areas, such as knowledge, wisdom and love that process of growth will hopefully continue right through life. A new-born baby is completely unable to survive independently and interacts with the world only on the instinctive level of reflex. Nevertheless, it is alive and has a right to life. Crimes of abuse and neglect of babies horrify us at a very basic, instinctive level. Legal protection of the right to life (as with other basic rights) is especially important for the vulnerable and defenceless – adjectives that certainly describe new-born babies.

Nestled inside the protective womb, attached to an automatic, biological support system, the day before its birth that baby is arguably less vulnerable and better protected than the day after its birth. Is there something about the process of birth which confers life upon it? Perhaps taking its first breath, or cutting the umbilical cord? Although these are hugely significant milestones in the journey of development, I don’t believe they mark the beginning of life. Developmentally speaking, it is ready for birth. It is at a stage at which it could be inside or outside of the womb, depending on the vagaries of the timing of onset of labour. Losing a baby in late pregnancy is devastating. We would expect the parents and wider family to mourn such a tragedy. Mourning is something we do when we lose a life, not when we lose an object.

Under UK law, there is a statutory offence of child destruction:

“…any person who, with intent to destroy the life of a child capable of being born alive, by any wilful act causes a child to die before it has an existence independent of its mother, shall be guilty of felony, to wit, of child destruction, and shall be liable on conviction thereof on indictment to penal servitude for life.”

This instrument is not widely used, but it has been used over the years to convict people for deliberately injuring pregnant women in such a way as to kill an unborn child. (To obtain a conviction, it must be proved that the defendant was not acting in good faith to save the life of the mother.) The threshold of determining whether a child is capable of being born alive was originally set at 28 weeks gestation, but later reduced to 24 weeks. This concept of viability of the unborn child is another moment at which one could consider that life begins. The trouble is that viability can only truthfully be determined after the event. In reality, there is no cut-off such as the law seeks to apply. The chances of survival increase with gestational age, but also depend on other factors not the least of which is the level of medical support available. And yet, whether or not something is alive cannot depend on the advancement or availability of medical science. Either an unborn child of 26 week gestation is alive or it isn’t, regardless of whether it is in 1918 or 2018 or whether it is in Germany or South Sudan.

Another option is to consider that life begins when the heart starts beating (usually at a gestational age of around 6 weeks). This is a tempting suggestion because it is something that can be detected reasonably accurately with modern ultrasound scans and it is one of the most important milestones in a pregnancy. However, it starts spontaneously, with no intervention from outside. It was an event that was programmed into the embryo – the embryo that has been changing and developing by itself, within the miraculous protective environment of a woman’s body, since the moment of conception. If that isn’t life, what is? And so, however I think about it, I can only conclude that life begins at conception. If sperm and egg do not come together then nothing happens. If they do, then a process has started that will, unless it malfunctions or it is interfered with, result in a new person. I am definitely pro-life, from the moment of conception.

How, then, do I resolve the clash between the woman’s right to choose and the unborn child’s right to life? Actually, I don’t think that such a clash is the real problem. The real problem lies in the fact that the world has chosen to tell a lie about contraception: that it gives us the power to completely separate sexual intercourse from pregnancy. It does, of course, hugely increase the level of control we have, but it does not give us total control. No method is 100% effective and we cannot control when the failures might occur. When we have sexual intercourse, therefore, there is always the possibility, however remote, of it resulting in pregnancy. On the other hand, when pregnancy is the desired outcome, stopping contraceptive use by no means guarantees that it will occur. Total control of such matters remains beyond us. The message that men and women choose whether to open themselves up to the possibility of pregnancy when they decide to have sexual intercourse is, I fear, not one that the world wants to hear. This doesn’t stop the message from being true. It is choice that should be made by both partners and for which both should be responsible. A pro-life message cannot, therefore exist in a silo. It has to exist alongside honest teaching about the responsibilities inherent in the choices we make regarding sex.

There are, sadly, occasions when we do have to resolve a conflict of rights. In the case of rape, a woman has already had her right to choose what happens to her body violated. If she becomes pregnant as a result then that is clearly a choice that has also been taken away from her. How she resolves the traumatic situation she finds herself in has to be her choice. Hopefully it is not a choice that she has to make alone, but in the end I believe it has to be her choice. I would still view an abortion as ending the life of the unborn child, but also recognise that the trauma may well be so severe that she feels unable to continue to carry the baby. If people were to clamour for someone to be held accountable for the death, I would be of the opinion that accountability lies with the rapist. Rape is a vile crime.

Another possible conflict of rights is between the right to life of a woman and the right to life of her unborn child. Well documented cases of this sort are often cited in abortion debates. Although rare, such events will occur and we need to be prepared to resolve them sensitively and compassionately. Again, hopefully the woman will not face that burden alone. Both the Eighth Amendment of the Constitution of the Republic of Ireland and the UK offence of Child Destruction recognise that such situations will occur. There are, of course tragic cases where both lives end up being lost, sometimes as a result of failure to correctly balance the competing rights. In other jurisdictions, legislation fails to address the reality of such conflicts at all, either in wording or implementation. Such stories are shocking and show us that some change is needed. However, the leap of logic that enables this particular correspondent to claim that such cases thereby prove that all abortion laws are both anti-women and anti-life escapes me. That is well below the standards I expect of The Observer.

Returning to the Republic of Ireland’s referendum, is abortion just a matter of personal morality that therefore requires constitutional change to allow choice? Although I live in a country that does not go in for a written constitution, I would agree with Ailbhe Smyth, leader of the Coalition to Repeal the Eighth Amendment, when she told the Guardian “The constitution should be the place for the values and aspirations of a society, not a place where you deal with the complexities and messiness of everyday life. That’s a matter for legislation.” However, when society regards matters of life and death as being part of the messiness of everyday life, I find myself calling into question the values and aspirations of that society. I believe the Irish constitution has currently got it right in recognising both the right to life of the mother and of the unborn child. Making this work in practice requires honesty about sex, honesty about life and honesty about abortion. Rather than staying in echo chambers, refusing to even hear – let alone acknowledge – the arguments of the other side, couldn’t people come together to have a rational conversation about how to find a better way to uphold a woman’s undeniable right to choose what happens to her body than terminating the life of an unborn child?

As I draw this post to an end, I find myself enveloped by an unexpected sense of calm. It is unexpected because, as well as being a divisive issue, abortion is an emotive issue. Generally, the emotions it provokes in me are anger and sadness. And yet, although the world seems to be moving inexorably in a direction with which I disagree (which usually strengthens these powerful emotions), I find myself, to borrow the title of a book I have recently read, surprised by hope: a hope that gives me the courage to keep on making the argument. I believe that there will come a time when future generations will look back on us in bemused horror that we could be so blinded by our pursuit of individual pleasure and individual rights as to treat the life of unborn children in such a disdainful manner (much as I hope the majority of people now look back in bemused horror on the slave trade). This change will come when someone of the stature and courage of Wilberforce stands up to call out abortion for what it is and declares, to borrow his words, “You may choose to look the other way but you can never say again that you did not know.”

The number or sermons that I remember from my undergraduate days – now over twenty years ago – can be counted on the fingers of one hand (with two or three fingers left over). One of these sermons concerned homosexuality. The suggestion that left a particular impression on me was that in reading into Paul’s letters a wholesale condemnation of homosexuality, the church may have thrown the baby out with the bathwater. Although I wouldn’t claim to be a perfect parent, I did manage to avoid throwing either of my babies out with their bathwater. The point of the saying, it seems to me, isn’t just, “Whoops! I didn’t mean to throw that away!” but rather that in disposing of something dirty you accidentally lose something that is really rather precious.

I have pondered the issue of homosexuality on and off over the (many) intervening years. I actually started writing this post well over a year ago. In the course of all that pondering and writing, I have come to understand why homosexuality is such a divisive issue for Christians. Reaching my conclusions has challenged me in all sorts of different ways, making me think much more deeply about what it means to be a Christian and, in particular, how I interpret scripture. Indeed, what I thought I knew about homosexuality in scripture was one of the barriers that held me back from fully embracing the Bible, Paul’s letters in particular. However, this was also one of the reasons that I eventually threw myself into studying the Bible in depth. In the end, I had to know. I shouldn’t have feared. What I got from studying Paul – someone whose writings I’d always found severe, impenetrable and hard to love – was a profound sense of liberation. A further surprise has been that I was unable to finish this article until I had not only looked to Paul but also looked forward to Revelation and back to Genesis.

In a previous post (Post-Truth Certainty) I wrote that “as human beings we crave certainty”. There is nothing that provides certainty as much as a rule being handed down to us, whether we certainly agree with it or certainly disagree with it. The power of this is multiplied if we see such a rule being handed down to us in a religious text. Homosexuality is one of those issues where many people see this happening: with the Bible unequivocally condemning homosexuality. Some people use this perception to reject homosexuals; others use it to reject Christianity. I understand only too well the attraction of such certainty, because I spent many years looking for such certain answers from outside. Such an approach seemed to offer insurance against getting it wrong and being one of the people of whom Jeremiah said:

Jeremiah 6:14

“They’ve healed my people’s wound too easily, saying “Things are well, they’re well,” when they’re not well”.

However, I now believe that this approach merely enslaves ourselves to a concept of law that Jesus came to liberate us from: a liberation that is one of Paul’s favourite subjects.

Let me be quite clear at this point that I am not dismissing scripture. It has a central role in my faith, as nicely described in one of the letters to Timothy:

2 Timothy 3:14-17

“But you, on the other hand, must stand firm in the things you learned and believed. You know who it was you received them from, and how from childhood you have known the holy writings which have the power to make you wise for salvation through faith in King Jesus. All scripture is breathed by God, and it is useful for teaching, for rebuke, for improvement, for training in righteousness, so that people who belong to God may be complete, fitted out and ready for every good work.”

I just don’t believe that the Bible is a rule book with which we can directly govern our lives. God works in a much deeper way through scripture. I recently became aware that in several places the Qu’ran refers to Christians as “people of the book”. In one sense this description is quite an honour, recognising as it does the importance that Christians at the time must have attached to scripture. Viewed from our present time, however, it appears somewhat incongruous, seeing as it is for Muslims that the ultimate revelation of God is a book: The Qu’ran (believed by Muslims to be a perfect copy of a heavenly work). For Christians, the ultimate revelation of God is not a book, but a person: Jesus. Of course, as primary source material, the whole Bible is vital for getting to know Jesus (including the Old Testament, which was the scriptures as far as New Testament writers were concerned). However, the point of Jesus’ ministry was that through our relationship with him we come to know God in a deeper, more mysterious way that the prophet Jeremiah foresaw:

Jeremiah 31:33

“Because this is the covenant that I’ll seal with Israel’s household after those days (Yahweh’s declaration). I’m putting my teaching inside them and I’ll write it on their mind; and I’ll be God for them and they’ll be a people for me.”

Returning to the subject of homosexuality, what does the New Testament say about it? It is directly referred to in three places, as follows (in Tom Wright’s “For Everyone” translation):

Romans 1:26&27

“So God gave them up to shameful desires. Even the women, you see, swapped natural sexual practice for unnatural; and the men, too, abandoned natural sexual relations with women, and were inflamed with their lust for one another. Men performed shameless acts with men, and received in themselves the appropriate repayment for their mistaken ways.”1 Corinthians 6:9&10

“Don’t you know that the unjust will not inherit God’s kingdom? Don’t be deceived! Neither immoral people, not idolaters, nor adulterers, nor practising homosexuals of whichever sort, nor thieves, nor greedy people, nor drunkards, nor abusive talkers, nor robbers will inherit God’s kingdom.”1 Timothy 1:9-11

“We recognise that the law is not laid down for people who are in the right, but for the lawless and disobedient, for the godless and sinners, the unholy and worldly, for people who kill their father or mother, for murderers, fornicators, practising homosexuals, slave traders, liars, perjurers, and those who practise any other behaviour contrary to healthy teaching, in accordance with the gospel of the glory of God the blessed one that was entrusted to me.”

Reading these verses, it is easy to understand why some people conclude that any expression of homosexuality is contrary to the will of God and is therefore morally unacceptable. However, I have found that reading these verses has raised some pressing questions in my mind, not the least of which is: “Why?”

Firstly, I’m going to consider the verses from 1 Corinthians and 1 Timothy together, because of their similarity: they are both lists of immoral behaviour. (There is a another example of such a list in Galatians 5:19-21, but that one doesn’t mention homosexuality.) In these verses, Paul isn’t providing a detailed exposition on these behaviours, but using them as examples of people who will not inherit God’s Kingdom (in 1 Corinthians) and of people who are not in the right (in 1 Timothy). Amongst the items in these lists, it is only the inclusion of homosexuality that troubles my conscience. Consciences are important, God given, tools that (providing we have nourished them with scripture) we should not ignore:

1 Timothy 1:18&19

“I am giving you this command, Timothy my child, in accordance with the prophecies which were made about you before, so that, as they said, you may fight the glorious battle, holding on to faith and a good conscience. Some have rejected conscience, and their faith has been shipwrecked.”

When my conscience is troubled, I want to understand why. After all, through wisdom and knowledge, guided as always by love, we should be able to tell the difference between right and wrong:

Philippians 1:9-11

“And this is what I’m praying: that your love may overflow still more and more, in knowledge and in all astute wisdom. Then you will be able to tell the difference between good and evil, and be sincere and faultless on the day of the Messiah, filled to overflowing with the fruit of right living, fruit that comes through King Jesus to God’s glory and praise.”

Within the Anglican framework of scripture, tradition and reason, it is incumbent on us all to use our reason to support or challenge the traditions we have inherited for the interpretation of scripture. Using my reason to follow each of the behaviours in the lists from 1 Corinthians and 1 Timothy to their logical conclusion, I very quickly reach a point where they will clearly inflict pain or damage on people and therefore also on the one in whose image all people are made: God. The exception is homosexuality. When I consider homosexuality in such a way, my reason cannot reach such a point. I have tried to see the evil consequences of two people of the same sex committing to living together faithfully in the service of God. I can’t find any. At this point, the obvious question to ask is whether what I have in mind when I consider homosexuality is actually what Paul had in mind when he wrote his lists.

A few years ago I read a fascinating book about the history of marriage. This clearly illustrated how much the idea and understanding of marriage has changed over the centuries and yet how all these different understandings are comfortably described by the single word marriage. The same could be true for homosexuality, with the added complication that I only read scripture in translation, not its original language. The world we know now is, of course, very different in many ways to the Greco-Roman world that Paul knew. In the Greek world, homosexuality was often part of the older teacher / younger student path of learning, with the older man expected to desire the younger while the younger man was not expected to enjoy his purely passive sexual role. In the Roman world, men were expected to be highly sexually active, including with male slaves. It was, however, frowned upon for Roman men to assume a passive sexual role: that was for the slaves. In both of these models there is a clear lack of mutuality and an equally clear imbalance of power. If I was to apply modern terminology to describe them I would probably choose “sexual abuse” or “rape” and have no problem in including them in the lists in 1 Corinthians and 1 Timothy. But was this what Paul was referring to?

Some authors (including Tom Wright – my trusted guide through the New Testament) argue that, whilst all the above is true, there were also mutual, meaningful relationships between members of the same sex in the ancient world, that Paul would have known about them and that by not differentiating he therefore condemns all homosexual behaviour. However, I don’t see how we can be sure about what Paul would or would not have known about. One way in which people try and determine this is to consider the precise meaning of the Greek words that Paul uses (malakoi & arsenokoita in 1 Corinthians and arsenokoita alone in 1 Timothy). Tom Wright, in 1 Corinthians for Everyone writes: “The terms Paul uses here include two words which have been much debated, but which, experts have now established, clearly refer to the practice of male homosexuality. The two terms refer respectively to the passive or submissive partner and the active or aggressive one, and Paul places both roles in his list of unacceptable behaviour.” It seems to me, however, that the use of different terms for different roles in a sexual act is very much indicative of the abusive Greek and Roman behaviours outlined above with their clearly delineated roles. Furthermore, I wouldn’t begin to characterise heterosexual relationships in their entirety by reference to a single sexual act that a couple might choose to engage in. Whilst interesting and informative, I’m not sure that this avenue can answer the question “what exactly was Paul referring to?” with any degree of certainty. I’m reminded of the following words:

2 Timothy 2:14

“Remind them about these things; and warn them, in God’s presence, not to quarrel about words. This doesn’t do any good; instead, it threatens to ruin people who listen to it.”

The point that I would take from this is that if the whole of this moral dilemma hangs on the interpretation of one or two words, it is far too much of a burden for mere words to be expected to bear. There is, for me, sufficient doubt for us to need to look for answers elsewhere, as authors on both sides of the argument do.

This is an appropriate point to move on to the passage from Romans. As with the other two passages, Paul isn’t writing about homosexuality as his main theme. At this early stage of the letter we are at the beginning of a long, complex argument for which Paul wants to establish as a starting point the broken state of humanity resulting from its rejection of God. In the eyes of many readers, the ultimate sign of this brokenness that Paul chooses to use is the existence of homosexuality. However, looking at the language of these verses, I don’t see a description of homosexuality as I understand it. I wouldn’t describe a loving homosexual couple as being “inflamed with their lust for one another” and more than I would describe a loving heterosexual couple in that way. It is the language of uncontrollable sexual appetite. There’s plenty of that in the world and it causes plenty of damage to the world, but it doesn’t describe two men in a loving, committed relationship. Furthermore, how are we to understand “swapping natural sexual practice for unnatural” or “abandoning natural sexual relations” in the context of people who have only ever been attracted to other people of the same sex? Whilst some people question whether homosexuality is a state into which people can be born, I have heard, seen and read enough testimony from homosexual people to be convinced that it is.

The discussion above is, however, something of a digression. The passage from Romans 1 is not an argument about personal morality (in the way that the passages from 1 Corinthians and 1 Timothy are). It does not argue that individual people engage in the homosexual activities described (however we understand them) because of their individual disobedience to God. It argues that the existence of these behaviours in their deviation from the created order of Genesis 1-2 results from the disobedience of the whole of the human race. Therefore, even if we accept the Paul is talking about all expressions of homosexuality, since his argument works at the population level, not at the personal level, using it to justify any conclusions we might wish to draw about personal morality and choices would be to miss the point entirely. To shed further light on this, we need to reflect on creation.

There are, of course, two accounts of creation in Genesis. In the first account, human beings are created on day six as the final act of creation:

Genesis 1:27-30

So God created human beings in his image. He created them in the image of God. He created them male and female. God blessed them, and said to them, “Be fruitful, be numerous, fill the earth and master it, hold sway over the fish in the sea, the birds in the heavens, and every creature that moves on the earth.” And God said, “Now. I give you all the plants that bear seed that are on the face of all the earth and every tree with fruit that bears seed. These will be your food. To all the creatures of the earth, to all the birds in the heavens, and to all the things that move on the earth that have living breath in them, I give all the green plants as food”. So it came to be.

In the second account (Genesis 2), God starts by making a single human being and then placing that human being in a garden called Eden “to serve it and look after it”. God then gives the human being permission to eat from any tree in the garden apart from one. God decides that the human being should not be alone and so sets about creating a helper. Having created a load of animals without finding a suitable helper, God then creates a woman from one of the human being’s ribs (at which point the term man enters the text) and the human being declares: “Well! This one is bone from my bones and flesh from my flesh! This one will be called ‘Woman’, because from a man this one was taken.” There then follows what sounds like something of an editorial comment: “Hence a man leaves his father and his mother and sticks to his woman and they become one flesh.”

What, then, can we glean about God’s original created order from these stories? Firstly, in both accounts human beings are allotted a plant-based diet. Eating meat is a later concession by God. It is possible, therefore, to view vegetarian people as modelling God’s original created order and the eating of meat as a deviation from that created order and as such a sign of humanity’s disobedience to God. This doesn’t mean that I feel the need to condemn other meat eaters (including myself) as immoral. Secondly, it would appear that the pairing up of male and female was indeed part of God’s original created order. In the first account, male and female are created together and told to be fruitful and multiply; in the second account the female is specially created as a helper for the male. It is possible, therefore, to view heterosexual people as modelling God’s original created order and homosexuality as a deviation from that created order and as such a sign of humanity’s disobedience to God. This doesn’t mean that I feel the need to condemn homosexual people as immoral any more than I do people who remain single or couples who are unable to be fruitful and multiply.

One further thing to note is that arguments against homosexuality that point backwards to creation often make far more of the difference between male and female than I can see in Genesis 1-2. Such arguments are often based on a perceived fundamental difference between men and women that is seen to be enshrined in creation. As Tom Wright notes in Romans for Everyone, “Males and females are very different…” Heterosexual relationships are then viewed as unions of difference, contrasted with homosexual relationships viewed as unions of same. In the first account of creation, male and female are created together and then jointly blessed and commissioned to be fruitful and master the earth. There is no indication of them being given different roles to perform. Although in the second account the woman is created to be a helper for the man this does not imply subservience, since God is often described in the Bible as our helper. When the man first sees the woman the thing he remarks upon is the similarity between them, not the difference (“bone from my bone, flesh from my flesh”). Therefore, when thinking about God’s original created order, equality of the sexes seems to be the order of the day (apart from the different reproductive roles). The view of the sexes as binary opposites is, I believe, incredibly damaging, but that is another topic for another day.

Until recently, however, in thinking about the specific issue of same-sex marriage I used similar arguments in considering whether there should be some equal but different classification for same-sex couples. The argument I was favouring went something like this. Since men and women are different, a relationship between a man and a woman is different to a relationship between two members of the same sex, not least in the possibility of procreation. Therefore, whilst I had become certain that a relationship between two people of the same sex should be treated as being equal to heterosexual marriage, I wondered whether the attempt to make them the same was one of those occasions when fairness was being confused with equality. Pondering on this, whilst driving home from work one day, I was suddenly struck by the following verses from Paul:

Galatians 3:27&28

“You see, every one of you who has been baptised into the Messiah has put on the Messiah. There is no longer Jew or Greek; there is no longer slave or free; there is no ‘male and female’; you are all one in the Messiah, Jesus.”

These are very familiar verses, speaking of healing the major divisions in the societies that Paul would have known. Slavery was a fact of life in the ancient world. The division between Jewish Christians and Greek (Gentile) Christians was something that Paul wrote at great length about, trying to heal. It was the full force of the third part of this that struck me on that drive home. If in the Messiah – in the age to come – there is no male and female the solid foundation of my argument above crumbles to dust. The possibility of procreation remains as an undeniable difference, but what about beyond that? There is surely far more to a marriage than procreation, but Genesis sheds little light on this (as it sheds little light on marriage at all, at least as we understand it today). To understand this further we need to turn around and look in the opposite direction.

As a Christian I not only look back at creation to understand the way things are, but also try and look forward into the age to come to try to understand the way things will be. It is time, therefore, to return to those signs of humanity’s waywardness and turn them around so that they point forward into the age to come, rather than backward towards creation. Thinking first about diet, I can well imagine that in the age to come (after the renewal of creation, when heaven and earth are joined and finally God’s kingdom comes on earth as it is in heaven) that, in our resurrected bodies, we will be quite content to eat plants (if food is even required for our new bodies) and live in harmony with the animals. When it comes to diet, therefore, it is possible to view vegetarian people as a sign that points both back to creation and forward to the age to come. But what of sexuality? We’ve seen that, arguably, heterosexuality is a sign that points back to creation, but does it point forward to the age to come? In one of those rare concrete views into the age to come, Jesus tells us that marriage will not survive:

Luke 20:34-36

“The children of this age”, replied Jesus, “marry and are given in marriage. But those who are counted worthy of a place in the age to come, and of the resurrection of the dead, don’t marry, and they are not given in marriage. This is because they can no longer die; they are the equivalent of angels. They are children of God, since they are children of the resurrection.”

On first consideration, this seems rather disappointing: I rather like being married to my wife. However, if we look deeper into marriage (beyond its function as a stable base for procreation and a safe space for the expression of sexuality) it is about love. Brought together by sexual attraction, held together by covenant vows made before family, friends and God, growing together through emotional love, the intimacy of marriage provides a space for that emotional love to evolve into that deeper love that Paul writes so eloquently about in 1 Corinthians 13: the love that is the one thing that will survive into the age to come. At least, that’s how it seems to me. Although, as I noted earlier in relation to creation, at one level we are all similar regardless of sex, at another level we are all uniquely created and so are all different. In this age, it is enough of a challenge to achieve the intimacy of marriage with one similar-but-different person. However, if we do achieve this then the love that then evolves can spill out to nourish our other relationships. This process is not dependent on having biologically differing reproductive roles. In the age to come, there will be neither male nor female because in our eternal resurrection bodies there will be no need to reproduce. In the age to come, I believe we won’t need to marry because we will achieve that beautiful loving intimacy that we strive for in our earthly marriages in all our relationships, in which sex will have no relevance because it won’t then exist. So, whilst heterosexuality points us back towards creation, same-sex marriages give us a glimpse into the age to come. Such glimpses, coming as they do like puzzling reflections in a mirror or as though through a darkened glass, are something really rather precious indeed.

How is Brexit going? Well, time is running out and the government still seems unable to agree about what they want to try and achieve. The problem is that the referendum solved nothing. The Conservative Party remains bitterly divided and so the government remains bitterly divided. Opposition MPs are caught, as they always are, between saying what they believe and saying what is politically expedient in order to weaken the government. Parliament, therefore, is also bitterly divided. Because of this, the issue of EU membership will continue to haunt us for decades, regardless of what sort of Brexit we end up getting, or even whether Brexit happens at all.

The problem is that the referendum was always about winning and losing so it created winners and losers, who continue to see the issues around EU membership (not to mention each other) in black and white. There’s nothing like winners behaving like winners to magnify the negative feelings associated with losing. There’s a reason why “loser” is such a toxic form of abuse in schools up and down the country. Losing is always hard to accept, especially losing by a narrow margin. Had the result gone the other way, I doubt that the leaders of the Leave campaign would have accepted losing by such a narrow margin and channelled their energies into making our continued EU membership work. They would inevitably have “carried on the fight”. Having winners and losers inevitably prevented us from working together afterwards. Our inability to work together is what is handing all the cards in the negotiations over to the EU. It could have been different.

Democratic politics should be about taking decisions collectively in order to avoid having a battle with winners and losers. The referendum could have been about taking such a collective decision on a complex topic in its varying shades of grey. This would have allowed us all to recognise the decision and then try and make it work together. This might be beginning to sound like some sort of tabloid “Remoaners” rant, but I’m saying something profoundly different. It is not about some people having to swallow their pride after the result and accept defeat. That would be a cruel thing to say: when people lose something they care deeply about they are bound to need a lengthy period of mourning before they can even begin to move on. No, taking a collective decision means everyone has to swallow their pride before the decision making process even starts by acknowledging that the decision taken might be one with which they disagree. That way there are no winners and no losers, just a collective decision that has been made by a process that everyone acknowledged.

Unfortunately, this problem is not unique to the EU referendum, but is endemic in our politics as a whole: we have turned it from a method of collective decision making into a battle with winners and losers. This is inevitable when political parties dominate the scene. They are the armies we create to fight the political battles we seem compelled to seek. At a general election, voters in each constituency should be collectively choosing one person to represent them in parliament. However, because of political parties we have winners and losers. It becomes all about parties winning or losing constituencies rather than about individuals being collectively chosen to take on the responsibility of governing the country.

In parliament, all MPs should be equal in having been chosen to represent their constituents. However, because of political parties they are labelled as winners and losers and physically divided along those lines by the design of the Commons Chamber. The government is formed from amongst the winners. The losers are frozen out. Hence our governments are never representative of parliament and so are never representative of the people (except, perhaps, in representing our collective unwillingness to enter into collective decision making). The government could be chosen so that all MPs have a stake in it so that, by extension, we all have a stake in it.

I would like to finish with some hopeful solution to the Brexit chaos but, as we have seen, the disease of winners and losers is so endemic in our politics that it is difficult to see a way forward. I understand the calls for a second referendum. However, unless it were to be about making a collective decision rather than being another battle to be won or lost it could only solve what the first referendum has already solved: nothing.

As Lent comes around once again, many Christians turn to fasting (often by giving something up), just as people of many other religions turn to fasting at the appointed times in their own seasonal cycles. There’s a trend these days for “giving up” something that isn’t good for us or for society to be coupled with “taking up” something that is good for us or for society. Good works are, of course, to be valued and no doubt this trend is well-intentioned. However, I think there’s a danger of this trend diminishing the value of fasting by giving the impression that fasting is a shallow, selfish act only for personal benefit: something that it is meaningless unless we also bow to the worldly cult of busyness.

To understand fasting better, I have recently been pondering some words of the Log Lady*:

“Food is interesting. For instance, why do we need to eat? Why are we never satisfied with just the right amount of food to maintain good health and proper energy? We always seem to want more and more. When eating too much, the proper balance is disturbed and ill health follows. Of course, eating too little food throws the balance off in the opposite direction and there is the ill health coming at us again. Balance is the key. Balance is the key to many things.”

For me, balance is indeed the key to many things. A balanced diet is certainly the key to physical good health. Balance in all our desires, not just in our appetite for food, is the key to mental good health:

“Are our appetites – our desires – undermining us? Is the cart in front of the horse?”

Mental illness, such as depression, is very adept at using our appetites to undermine us. It can persuade us that giving in to the urge to overindulge will make us feel better, only to castigate us as failures when we achieve this readily attainable imbalance. Alternatively, it can persuade us that the only solution is to deny all our desires at once, only to castigate us as failures when we don’t achieve this unattainable imbalance. These are all part of the power games that make us hide from ourselves:

“Sometimes we want to hide from ourselves: we do not want to be us. It is too difficult to be us. It is at these times that we turn to drugs or alcohol or behaviour to help us forget that we are ourselves. This, of course, is only a temporary solution to a problem which is going to keep returning and sometimes these temporary solutions are worse for us than the original problem.”

When we hide from God, as in Eden, we are also hiding from ourselves. It is only when we are prepared to embrace balance in our lives and stop hiding from ourselves that we stop hiding from God. Thus, as well as being the key to physical and mental good health, balance is also the key to spiritual good health. In balance we see truth. In truth we see God.

How we go about achieving balance in our appetites is bound to be a very personal thing. For some, directly confronting particular appetites that tend to control them will be the way. For others, confronting one particular appetite and bringing that into balance will be a means of bringing their other appetites into balance too. This may even involve giving up the same thing year after year. Whilst this may appear tokenistic (perhaps as being merely a dietary aid), for the person involved that one thing may be the key to bringing everything else back into balance and creating that space in their lives within which to see God.

Seeing God is an end worthy of itself. It is what we were created for. When we see God – when we achieve that balance in our lives – the good works will follow, although they might not be the works that we would have chosen by ourselves. By all means take something up for Lent, but don’t give up on giving up.

* The Log Lady is an enigmatic character from the enigmatic TV series Twin Peaks: “Who’s the lady with the log?” “We call her the Log Lady.”

One thing that my former prejudices about Roman Catholicism (more of which another time) denied me was learning from the example of Mary. Whilst I haven’t come to embrace all the traditions that have built up around her over the centuries, I have managed to look beyond my prejudices and learn from what we know of Mary from scripture. In particular, I often think of her tendency to treasure and to ponder.

When the Angel Gabriel greeted Mary before going on to announce that she was going to have a certain baby (Luke 1:29): “But she was much perplexed by his words and pondered what sort of greeting this might be.” Then, after the shepherds had visited the manger and told their story (Luke 2:19): “But Mary treasured all these words and pondered them in her heart.” Again, after finding her lost twelve-year old son debating in the temple (Luke 2:51): “Then he went down with them and came to Nazareth, and was obedient to them. His mother treasured all these things in her heart.” (All quotes from the NRSV.)

Justin Welby, in his Ecumenical Christmas letter, wrote about the need for the good news of Christmas in a world increasingly poisoned by fake news: “deliberate misinformation published in order to deceive, to confuse and disrupt”. The best way I have found to determine truth in a complex world poisoned by fake news is to treasure the words I hear and ponder them in my heart. I find that this way, truth is eventually revealed. The process requires patience: it happens in God’s time rather than in the world’s time. However, it is the world’s insistence on instantaneous, straight-forward, dogmatic decisions that leaves us vulnerable to fake news in the first place.

There is another side to the fake news phenomenon: the temptation to dismiss perplexing truth as fake news. Although this is perhaps most clearly embodied in Donald Trump, I think it is a very human tendency. Why might truth be perplexing? Well, it might be more complex than we want it to be and therefore require more of our time than we want to give. It might inconveniently contradict an argument we are trying to make at the time. More seriously, it might challenge our whole world view and the inherent prejudices therein. These are all things that push us to dismiss truth as fake news. Mary, although perplexed by an angel’s greeting, didn’t dismiss it as fake news. She pondered what its meaning might be.

This Christmas, if you haven’t truly heard the love song that the angels bring, try holding the story of Jesus in your heart and take some time to ponder it. Ask yourself whether you haven’t, perhaps, dismissed as fake news a perplexing truth that might actually be good news: something, indeed, to be treasured.

One summer – the year that Charles and Diana got married as it happens – whilst packing for our family holiday, my parents queried my choice of book. They suggested that I might like to choose something different or at least pack something else as well, just in case I got a bit bored. At the age of six, I wasn’t having any of it. I was convinced that I knew best: the book I had chosen contained lots of good stories. I knew this because I had heard some of them before. Furthermore, it had plenty of new stories for me to explore. It comprised 1,152 pages and (as the internet now informs me) 783,137 words, so was bound to last me the whole holiday. It was, as the title of this post makes no effort to hide, the Bible. Not just any Bible, but my very own compact (14.4cm x 9.5cm x 3.2cm) copy of the King James Version of the Bible, which I had recently received as a prize for regular attendance at Sunday School. Needless to say, on the first shopping trip on reaching our holiday destination a couple of comics had to be hastily acquired to stave off my complaints of boredom. Inauspicious as it was, this was the start of a relationship with a book that, thirty-six years later, I can’t drag myself away from: a book that keeps on giving.

Although, as I described at Easter, I could see that that somewhere amid the curious stories (that I didn’t fully understand) in the Bible was a message about a better way of living than what I saw in the world around me, I have not always found regularly personal reading of the Bible myself an easy thing to do. There were times when I made an effort, but it always felt like a duty or chore that I made myself do before bed, after reading a chapter or two of a good novel. There were also plenty of times when I made no effort.

I tried several different ways of reading the Bible. Since many people I know find these helpful, I tried daily Bible reading notes. However, I found two stumbling blocks with them. Firstly – perhaps it is the completest Doctor Who fan in me – I found reading excerpts, out of order to be rather unsatisfying. Was I understanding it correctly out of context? What about the bits that were getting missed out: weren’t they important? Secondly, having set daily readings was stressful: getting ahead wasn’t allowed and getting behind made me feel bad about myself.

At other times I tried reading whole books (I particularly remember doing this with Luke and Acts) unaided, but although I felt a certain sense of achievement, I also felt frustrated: much of the material was rather puzzling and true understanding felt unattainable. On a further occasion, I obtained a couple of weighty tomes of study notes and ploughed through a substantial section of the Old Testament (Genesis to somewhere in the region of Kings or Chronicles), referring to my study notes as I went along. To a certain extent – on an intellectual level – this helped, but there was still the nagging frustration of not fully understanding. Furthermore, the books I’d bought were too big to ever take out of the house with me!

One day (it must have been at least 10 years ago) I was browsing in a Christian bookshop and came across Tom Wright’s “New Testament for Everyone” series. I immediately sensed that these were the books for me. In these books, the author provides his own translation of the original Greek text and intersperses it with his own commentary. These books, therefore, are structured quite like some daily Bible reading notes, but work through complete texts with no schedule to limit my reading or make me feel guilty. Whilst the commentary sometimes provides historical and textual details to help the reader more fully understand the meaning of the text, it concentrates on providing (by mining a seemingly endless supply of appropriate anecdotes) a sense of how each passage might be relevant to the reader today. I bought the volume on Luke’s gospel. However, although I read this and collected a few more volumes, there still seemed to be barriers in place. One of these barriers was that I hadn’t yet learned to look beyond the narrow confines of factual accuracy to see a deeper truth. The other barrier was fear: fear that I wasn’t able to measure up to the demands of the Bible; and fear that I might find something in the Bible that I wouldn’t be able to accept.

Something changed for me last year. Just before going away for a week I picked one of the many unread volumes (“Paul for Everyone: The Prison Letters”) off my shelf and took it with me. I started reading it and found that the fear had gone, allowing me to see more clearly. This is partly due to my depression lifting: it was very adept at twisting things that should be helpful into sticks with which to beat myself (hence the fears of not measuring up). However, as I get older I also feel I have a better understanding of the human condition and God’s grace. Although I still maintain an interest in such issues, I am able now to put aside distracting obsession with factual accuracy, secure in that knowledge that the Bible contains a deeper truth of infinitely greater value. When I come up against the things I feared being unable to accept I often find that when I better understand the text the problem melts away. This might be because I was asking the wrong question, or because I had too narrow, literal understanding of the text, or because the process of reading, thinking and praying changes me, like any meaningful act of learning should. How many times did Jesus say the words “Do not be afraid!”? Perhaps, as much as I like to complicate things, it is as simple as that.

It wasn’t, therefore, just that I had found the right books to help me read the Bible, but I also had to wait for the right time. And, I now realise, the right time rests on all those tentative false starts, all the experiences I have lived through, all the conversations I have had and all the fragments I have picked up from sermons, homilies and courses over the years. None of it was wasted effort. Suddenly the conditions were right for all those seeds planted by many people over many years to suddenly burst into life. The most exciting thing about the moment when seeds burst into life is that it is only the start of an exciting journey of growth and development. Since then I have worked through most of Tom Wright’s volumes on the New Testament (with a brief diversion into some of the similar volumes that John Goldingay has written for the Old Testament). These books are teaching me to read the Bible for myself. Although I generally agree with these authors, I’m never afraid to disagree with them and to prayerfully draw my own conclusions.

As I meander towards the end of this post, I feel a very human desire to produce some intellectually rigorous example that will convince anyone reading that I am right. A moment’s pause, however, reveals that this would be to miss the point entirely. What I’ve been talking about is a relationship with a book and relationships can only be built by the people involved, who have to learn to trust for themselves. As with building any relationship, you may need to confront your fears and you may need to be patient. However, you don’t need to do it alone. If you have never tried to read the Bible before: take the plunge. Whatever you think you know about it, you’ll find it to be quite different – I frequently do. If you are one of the many people hovering on the edge, who I’ve heard say things like “I agree with Christian values, but I’m not into the whole religion thing”: you’ve sensed something of value, but there is so much more to discover. If you have tried and found it a struggle: keep persevering, because your time will come. To everyone: find your own way to read the Bible. Let it shape you and help you to grow. I can’t prove anything to you. All I can do is to bear witness to the truth that I see: the Bible is a book that keeps on giving.

In the early hours of Sunday the 5th of August 1917, the 19th Battalion were making their way from Fosse 10 to the Laurent sector of the front line. Troops were often at their most vulnerable when on the move and so it proved on this night. At some point along their route, a shell landed by the side of the road along which they were marching. The casualty message for the day reported: Sick – Nil; Killed – 1 Other Ranks; Wounded – 7 Other Ranks; and Wounded at Duty – Lieut F H Cantlon.

In a war of the scale and horror of this particular war, these figures may not seem all that remarkable. However, this do not mean that the results are any less devastating for the men involved or for their parents, wives and children. The devastating significance for our story is that the one other rank killed had a name: Wilfred Kibble. The official report of Wilfred’s death states that he was killed instantly. Whilst letters written to Wilfred’s mother in the weeks after the event aren’t unanimous on this point, they do agree that he didn’t suffer for long.

As I look into Wilfred’s young eyes staring out at me from his In Memoriam card above, I think of those verses from Laurence Binyon’s poem “For the Fallen”:

They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old:

Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn.

At the going down of the sun and in the morning

We will remember them.

Until I looked it up this morning, I hadn’t realised that these words (published in The Times on the 21st of September 1914) were written so early in the war. They shall grow not old. Contrary to the current cult of youth, young adults are not a finished product, destined only to be wearied by age, decline in wisdom, be marginalised by society and become bitter like a cheap table wine. They are people who have reached the starting line of life, who have the opportunity to mature as they age like a fine wine by growing in wisdom, developing in understanding and then offering back what they have learned to society. That is what being human is about. Wilfred, and millions more like him from this war and so many other wars, have been robbed of this opportunity. Not by a shell fired by a German soldier, but by our collective unwillingness to listen to the past and learn how to live in peace with one another. That’s the real tragedy of war.

We must remember them.

I always find that a map helps and have therefore plotted various places that I mentioned in my last post on a Google My Map. In particular, I have worked out where Fosse 10 was located and have marked its location along with Verdrel, Coupigny, Marqueffles Farm and Maroc. The approximate position of the section of the line that the 19th Battalion held for the two periods in July 1917 is marked as “Lens Sector Trench”.

Further information suggests that the offensive that the 19th Battalion were preparing for while at Fosse 10 at the end of July was an attack on Hill 70, to the north of Lens. This was planned for the end of July as a diversionary tactic to draw German troops away from Ypres. The offensive was delayed due to bad weather and the Battle of Hill 70 eventually began on Wednesday the 15th of August.

August 1917 started with the 19th Battalion still acting as Divisional Reserve stationed at Fosse 10. On Saturday the 4th of August, orders were received to relieve the 31st Battalion in the front line Laurent Sector. I’ve marked the approximate position they took up on the map as “Laurent Sector Trench”. It is north-west of the centre of Lens, whereas the Lens Sector Trench was south-west of the centre. A note on the standard message pad records the battalion’s strength going into the trenches as 28 officers and 811 other ranks. As per their orders, the battalion set off at 9.15pm, aiming to have completed the relief by the early hours of Sunday the 5th.