I had never heard of Charlie Kirk until the news of his murder broke but as soon I was realised he was a close ally of Trump I started to assume that I would find anything he had said objectionable. However, in a much shared quote, Kirk said “When people stop talking, that’s when you get violence. That’s when civil war happens, because you start to think the other side is so evil and they lose their humanity.” That struck a chord with me because I had been thinking along much the same lines over the previous week.

On the previous Saturday, my wife and I had decided to spend our wedding anniversary bearing witness to our belief in the right to life from conception and our grave concerns about assisted suicide by joining the March for Life. After a gentle amble through the streets of Westminster we arrived in Parliament Square where there was also a sea of Palestinian flags (although we didn’t witness any of the 850 arrests that happened there that day). As we listened to the prayers and speeches organised for our event, I noticed some “pro-choice” counter protesters nearby and immediately felt an urge to go over and talk to them. It seemed to me that it would be a missed opportunity to come all this way and not take the time to listen to people with opposing views.

After a while, I plucked up the courage needed to talk to strangers and we went over to them. As soon as they realised that we had come over from the March for Life we were told in no uncertain terms that we had no right to come and talk to them. We tried to explain that we just wanted to talk and listen so that we could better understand each other. However, we were told that “We have nothing to say to you and you have nothing the say to us.” Since we all felt strongly enough about the same issue to turn out in Parliament Square on a sunny Saturday afternoon, it seemed to me that we all had a lot that we could say to each other. One lady did make an attempt to talk to us and started to explain that she had been raped. However, the others quickly closed ranks and the opportunity was lost behind a wall of “Don’t talk to them: they’re from over there!” As we took the hint and started to leave, I heard our brief point of contact say “But if we don’t talk to them, how will they ever understand?” Exactly.

I regret that we didn’t get the opportunity to listen to that lady’s story, had she wished to tell it. I regret that we didn’t get the chance to tell her that however different our views on abortion might be we would never judge or condemn her for the choice she made. I regret that we didn’t get the chance to listen and to talk. It seems to me that if we don’t talk to “them” because they are from “over there” and believe we have nothing to say to each other we are sowing the seeds of division that can spiral into conflicts like the very one in Gaza that inspired the more newsworthy protest on the other side of the square.

So, yes, I do agree with Charlie Kirk that when people stop talking, that’s when you get violence. However, it is a very superficial statement. There is no point talking to people if you don’t also listen to them and there is no point listening to them if you are not open to the possibility that you might learn something from them. Immediately before the quote I started with, Charlie Kirk explained, pressing his fists together as he did so, that he recorded his events and posted them on the Internet so that people could see “these different ideas collide”. He may have seen the need for people to talk to each other but he viewed that act of talking as conflict – a debate to be won or lost – not a conversation to enable learning, growth and understanding. He spoke violence in many other ways too. The quotes are out there; I have no wish to repeat them. I would just add to those words of his that I have chosen to quote a warning that if we speak violence, we seed violence.

In the primary school I work in, we have three basic rules plastered all over the walls: Ready, Respect, Safe. It is amazing how much of what we discuss with the children can be brought back to one of these three words. Over the past week, I have been reflecting on them in the light of Charlie Kirk’s killing and my experiences in Parliament Square. Are we Ready to learn from people with different opinions to our own? Can we Respect people by truly listening to them? And, when we speak, will we choose our words carefully to keep everyone Safe?

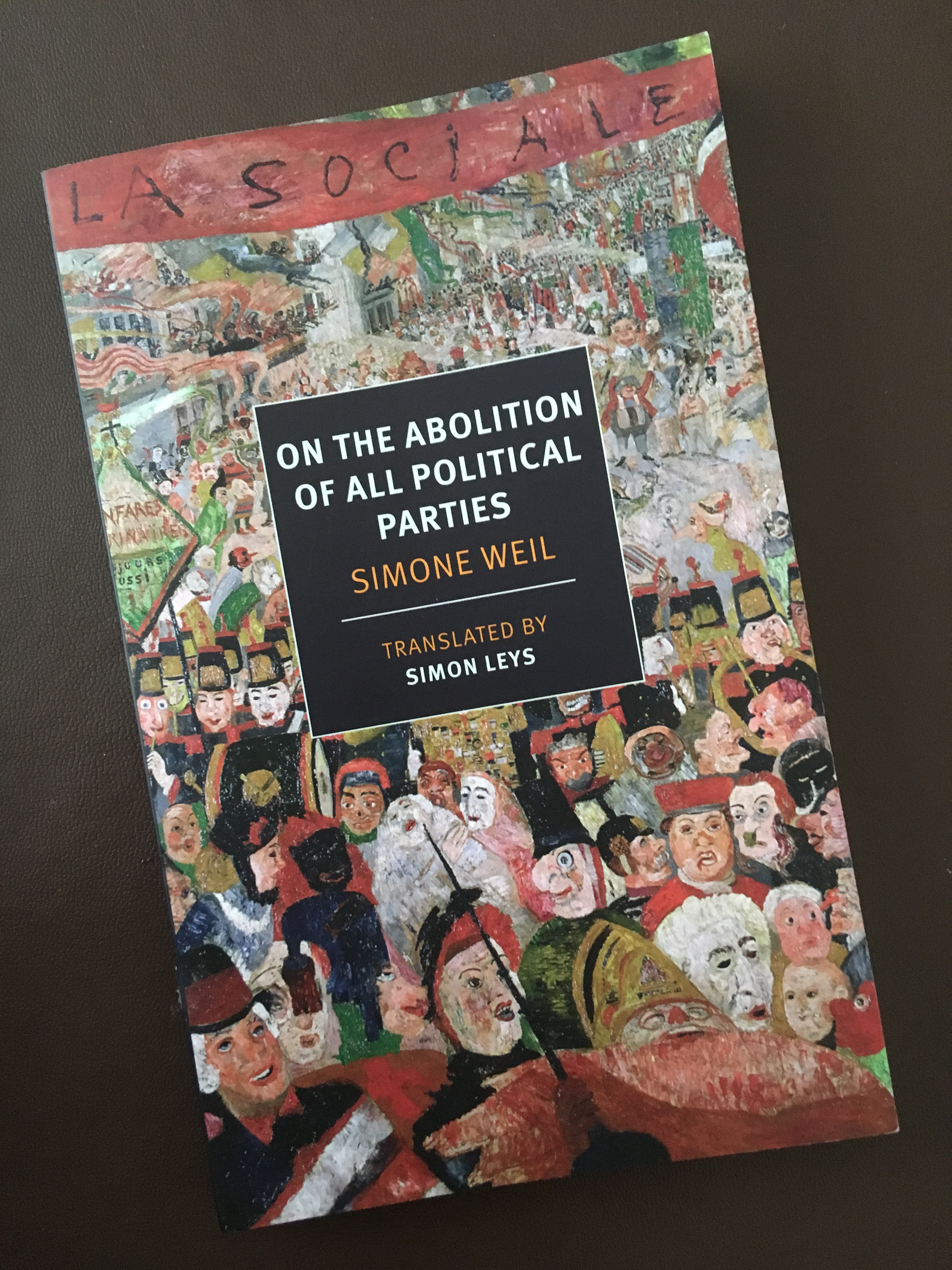

Following the resignations of several MPs from the Labour and Conservative parties back in February, I reviewed some of my writings on political parties. They started by my questioning the role of truth in our politics with some thoughts on the way politicians try to win our votes by feeding our desire for certainty about the future, when this is something that no one can offer with any degree of honesty (

Following the resignations of several MPs from the Labour and Conservative parties back in February, I reviewed some of my writings on political parties. They started by my questioning the role of truth in our politics with some thoughts on the way politicians try to win our votes by feeding our desire for certainty about the future, when this is something that no one can offer with any degree of honesty (