Last night, I attended my first ever general election hustings, in which the candidates for the Thornbury and Yate constituency faced questions from a local audience. As I’ve said recently on my blog, I think the dominance of political parties has separated us from the importance of choosing a candidate with the right range of skills and qualities to represent us at Westminster. I therefore hoped to get a sense of what the candidates were like as people. The Gazette has produced a live transcript of the event, so I won’t try and recreate that, but rather try and describe the impressions that the candidates made on me. Before doing so, however, I want to make a few general points about the questioning.

Questions, Questions

It was unfortunate that nearly all of the questions related to the major national issues (education cuts, social care, environment etc.) The result of this was that the candidates spent a lot of time quoting from their manifestos, rather than revealing very much about themselves and their own views. When talking about money, this generally involved Luke Hall (as the sitting MP from the governing party) blinding us with detailed figures and the other candidates obfuscating with commitments to spend billions here and billions there. The lack of any expert interpretation of such figures rendered much of the discussion meaningless. This is why I am not a fan of the televised leader debates. I think that a series of one-to-one leader interviews with a well prepared interviewer actually stands a much better chance of getting closer to the truth.

I had submitted some questions, although since I did so less than twenty-four hours before the event, I did not get a chance to ask any of them. As an indication of some of the things that might have interested me to hear the candidates talk about, here are my proposed questions, with a couple of notes of relevant comments that candidates made when answering other questions:

- When voting in parliament, how would you balance the competing demands of your constituents, your party whip and your own conscience and would your answer depend on whether you found yourself sitting on the government or opposition benches?

- What it your opinion about the UK’s national debt and how would your party’s policies impact upon it?

[Although it was not especially relevant, Luke Hall did raise the issue of the national debt in his response to the final question of the night. He pointed out that it is not just about leaving a large debt for future generations to deal with but also about the large sums we are paying each year to service that debt. I am really concerned about both aspects and I worry that the Conservative approach of austerity does not appear to be solving the problem and that none of the other parties really seem to have a plan for reducing it, or even for stopping it growing.]

- What could be done to address rising inequality in the UK?

- Is it the job of parents or of the state to feed our children?

- Is the proposed Trinity Lane housing development on the northern edge of St John’s Way, Chipping Sodbury an appropriate contribution to the national housing crisis?

- Please name one policy that you agree with from the manifesto of a party other than your own.

[Iain Hamilton mentioned that there was one – and only one – UKIP policy that he agreed with: raising the minimum wage. This was greeted with a volume of amused laughter that was only eclipsed when the Labour party representative accidentally referred to the Prime Minister as Margaret Thatcher. Furthermore, Iain talked on another occasion about the need for politicians to work more collaboratively across party lines and having the courage and confidence to use good policies that other parties have come up with.]

Brian Mead (Labour)

Since Brian couldn’t get time off work to attend, I was unable to form any impression about him. John Turner, who stood in at short notice, was very eloquent on behalf of the Labour Party’s policies. I note that Brian omitted to answer the following questions on his Bristol Post Candidate Profile:

- Why do you want to be elected as an MP?

- Why do you think you would be a success at the job?

- What would your main aims be during your term of office?

Claire Young (Liberal Democrat)

Claire struck me as being rather tentative and, given the importance the Liberal Democrats must have on regaining this seat I would have expected her to be better prepared. (I comment further on this below, in my discussion of Luke Hall.) She didn’t strike me as someone who really wanted to win this seat, but more as someone who had been reluctantly persuaded to stand. This does rather tie in with my observations regarding the generally poor quality of her campaign materials, many examples of which have come through my letterbox.

In addition, on several occasions she talked about what the Liberal Democrats would do if they were in a future government. Since, however, Tim Farron has ruled out a coalition with either the Labour Party of the Conservative Party, this isn’t going to happen. Given that she is the candidate with the best chance of unseating Luke Hall, I would feel more confidence in voting for her had she given any clues as to how she could make a difference for Thornbury & Yate from the position she would take up on the opposition benches, rather than talking about what her party would do from a position they have ruled out taking up.

Iain Hamilton (Green)

Iain has been the candidate who has been most openly active on Facebook, but some of this activity had given me concerns. In particular, I would mention his sharing of news stories from Russia Today and The Canary (which, as far as I can gather, has all the balance and accuracy of a kind of left wing Breitbart). Furthermore, when discussing the issue of Conservative election expenses on Facebook, he gave the impression of not affording Luke Hall the courtesy of the assumption of innocence until proved guilty that I hold as being an important component of the rule of law in this country. He did, however, have the grace to respond when I queried this – the only response I have had from any candidate to a question I have asked on Facebook. Despite these reservations, I do applaud his passion both for politics and for open engagement.

On the evening, I found Iain engaging and, although on occasion he didn’t answer the question that had actually been asked (which, it seemed, the audience was more forgiving of if your name was not Luke Hall) he did speak passionately on many issues. In particular, his passions for finding new ways of looking at long standing problems and – as I’ve already mentioned – for greater collaboration in politics shone through. As he said, the nature of the two-sword-lengths-apart debating chamber of our parliament (compared with the more common modern day circular designs) is symbolic of the problems with our current adversarial style of politics. Finally, the principal he mentioned of having a thirty year plan for things like education and the NHS, rather than major reorganisations every five to ten years matches up well with my own views.

Luke Hall (Conservative)

In his opening statement, I was concerned to note that Luke Hall repeated the implication he has also made on Facebook that a Conservative MP is more likely to have their voice heard at Westminster than an MP of another party. I queried this on Facebook the other day, “Luke, I worry about the implication in your post that a Conservative government would only listen to Conservative MPs. Surely our voice should be listened to in Westminster, whether or not our MP belongs to the party that forms the government?” I have yet to receive a response.

The first question was about school funding. When Luke Hall took his turn to answer, he rather aggressively questioned the other candidates before answering the question himself. In particular, he repeatedly asked Claire Young what the funding per pupil was in South Gloucestershire. After a couple of attempts at avoiding the question, she did admit that she didn’t know the figure off the top of her head. Luke’s point was that the figure had risen by over £200 per pupil per year and he was annoyed that this was being misrepresented in other parties’ campaign materials, particularly those of the Liberal Democrats. Now, since Claire Young is a local councillor and has been trying to gain a lot of political capital over the issue of school funding, I might have expected her to have had the figure to hand (if not in her head). Having said that, I wasn’t too surprised, given that when I asked for more detail a couple of weeks ago about her claims about school funding on a Facebook thread in which she was active, she failed to respond. However, the manner in which Luke Hall set about her did not, I suspect, win him many fans on the night. He came across more Westminster than Thornbury & Yate.

These type of events are always rather different for sitting MPs (especially if they belong to the governing party) than for their challengers. People will tend to take out all their anger about the problems of the world on them. This is yet another symptom of our muddled politics in which our local candidates have become the mouthpieces of one of a handful of political parties. On occasion Luke was treated rather rudely, which (as with his early treatment of Claire Young) was regrettable as it makes it much harder to get anywhere near the truth. He did, however, settle down and take it with better grace as the evening went on.

Candidates for governing parties are often more constrained in sticking to the party line than their opponents. Given this, I find it important to read between the lines in their answers. There were two such occasions when Luke made interesting comments that seemed, to me, to be challenging the official Conservative positions. On the issue of grammar schools, he made a point of addressing the unfairness of the 11+ by placing great emphasis on the need for multiple entry points at different ages, to reflect that fact the children mature academically at different ages. He also raised the idea of scouting to encourage more applications from disadvantaged pupils who are generally less likely to apply for grammar schools. Furthermore, these points were all framed within language about the policy that made great reference to “if, after consultation, this goes ahead” etc. I didn’t get the impression that he is convinced by the grammar school policy.

The other occasion was on the issue of fox hunting. The questioner asked whether the candidates would vote to reinstate fox hunting if the proposed free vote on the issue goes ahead. Luke started by saying that he thought this would be a bad use of parliamentary time, which seemed to me quite a bold statement for a Conservative candidate. He then stated that how he would vote would depend on the details of the legislation. Although I’m tempted to see fox hunting as a black and white issue that he should have given a clear answer on, issues are always more complex than they seem. After some reflection on comments I have previously made about the madness of voting for politicians based on promises they make long before the time when they actually have to decide, rather than choosing someone that we trust to make decisions as and when they arise, I would not be being true to those principals if I criticised him for this answer.

Conclusion

I am glad I went to hear the candidates speak and hope that I will make the effort to attend a hustings next time we have an election. To some extent, the emphasis on national policies got in the way of what I hoped to achieve: getting a feel for which candidate had the qualities to represent the constituency for the next five years. I have still not decided who I will vote for, or how I will decide, but the candidate that won me over most on the night was Iain Hamilton.

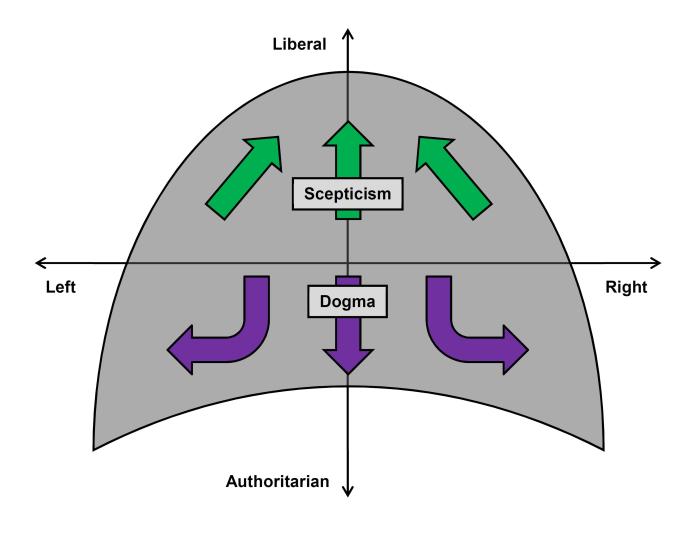

The enclosed, grey area crudely represents the region in which politics operates. I have already described how scepticism pushes us towards liberalism and dogma pushes us towards authoritarianism. Whilst such dogmatic authoritarianism can push us to more extreme left or right wing view, note that there is also a purple arrow going straight down. This represents what I mentioned above about it being perfectly possible to maintain centrist views, but in a dogmatic (and therefore authoritarian) manner. This is, I believe, where the politics of the centre often goes wrong. There is a prevalent belief that simply being in the centre, neither too far to the left nor too far to the right, means being liberal. This is not true. Being liberal is about the way in which you do politics. You can be a liberal in a right-wing party or a liberal in a left-wing party or even, although not necessarily, a liberal in a party which is called liberal. I believe that sceptical liberalism will pull you away from the extremes of left and right, but with significant flexibility to manoeuvre to the left and to the right to find the best solutions for the situation at the time you are looking and the policy area you are looking at. On the other hand, being in the centre probably protects you from the worst excesses of authoritarianism (totalitarianism – the pointy bits at the bottom left and right of the grey area) which probably only occur in far left and far right politics.

The enclosed, grey area crudely represents the region in which politics operates. I have already described how scepticism pushes us towards liberalism and dogma pushes us towards authoritarianism. Whilst such dogmatic authoritarianism can push us to more extreme left or right wing view, note that there is also a purple arrow going straight down. This represents what I mentioned above about it being perfectly possible to maintain centrist views, but in a dogmatic (and therefore authoritarian) manner. This is, I believe, where the politics of the centre often goes wrong. There is a prevalent belief that simply being in the centre, neither too far to the left nor too far to the right, means being liberal. This is not true. Being liberal is about the way in which you do politics. You can be a liberal in a right-wing party or a liberal in a left-wing party or even, although not necessarily, a liberal in a party which is called liberal. I believe that sceptical liberalism will pull you away from the extremes of left and right, but with significant flexibility to manoeuvre to the left and to the right to find the best solutions for the situation at the time you are looking and the policy area you are looking at. On the other hand, being in the centre probably protects you from the worst excesses of authoritarianism (totalitarianism – the pointy bits at the bottom left and right of the grey area) which probably only occur in far left and far right politics.