One day, sometime last year, I was walking across College Green in Bristol and observed a handful of people protesting in favour of repealing the Eighth Amendment of the Constitution of the Republic of Ireland which states:

“The State acknowledges the right to life of the unborn and, with due regard to the equal right to life of the mother, guarantees in its laws to respect, and, as far as practicable, by its laws to defend and vindicate that right.”

My eyes were drawn to one of the banners which read, “Hands off my ovaries”. “Why,” I wondered to myself, “would you go to all the effort of setting up a street protest and then display a banner advertising a total lack of understanding of the issue?” Firstly, the only way I know of to control ovaries is for their owner to choose to take the contraceptive pill, which then may or may not inhibit ovulation. Secondly, abortion is not about intervening with ovulation, but about intervening at a point in time after the ovaries have done their work.

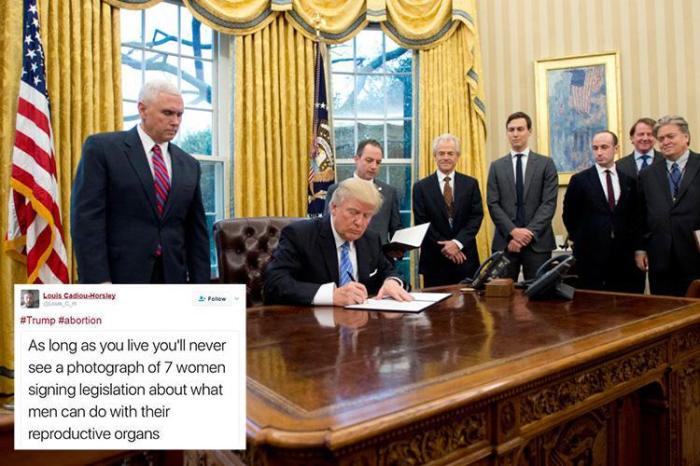

A similar level of misunderstanding was to be observed back in January 2017, when the newly inaugurated Donald Trump signed an executive order reinstating the Mexico City policy, which declares that organisations in receipt of US Federal funds “neither perform nor actively promote abortion as a method of family planning in other nations”. In particular, I remember the following picture being prevalent on Facebook:

Consider the caption. Firstly, only one man signed the order, not seven as stated (or even eight as pictured). Secondly, abortion is not about what women choose to do with their reproductive organs, but about what is chosen to be done to a new body growing inside those reproductive organs. The puzzling thing about all this confusion is that the nouns we use for the process (abortion or termination) are based on verbs whose meaning is quite clear:

abort: to cause to cease or end at an early or premature stage

terminate: to bring to an end; put an end to

An abortion or termination is, therefore, the act of ending a process that has already started; the process of growing a new human body inside a woman’s reproductive organs; the process called pregnancy.

The muddled campaign slogans I have observed are a result of the misinformation that stems from abortion being such a divisive issue. As divisive issues tend to do, it divides people. Once people are divided into two camps, true debate rarely seems to take place. Each camp ends up talking to their own members in language that alienates the other side. As a result, it is all too easy for them to never listen to what the other side is actually saying but only to hear them disagreeing with their own views. So pro-life activists only hear pro-choice activists denying an unborn child’s right to life and pro-choice activists only hear pro-life activists denying a woman’s right to choose. Indeed, pro-choice group Abortion Rights deliberately refers to pro-life groups as “anti-choice”. Similarly, pro-life group SPUC refers to “a radical anti-life agenda”. This makes progress impossible and leaves the many people in the middle struggling to make up their minds. How can you make a decision, with such lasting consequences, when all you can hear are contradictions? What are you supposed to think if you believe that life is precious and that people should have a choice about what happens to their bodies? Surely in the liberal society we are supposed to live in we should be able to talk about life and choice together?

“My Body, My Choice” – the slogan of choice for Abortion Rights – is an argument that resonates strongly, perhaps now (post-Weinstein and Me Too) more than ever. Of course women should have the right to choose what happens to their bodies. All people should have the right to choose what happens to their bodies. For too long, too many women have not had this control, whether through sexual violence or through the demands and expectations placed upon them by a patriarchal society. We should be horrified when any person is physically forced or manipulated by abuse of power into doing something unwillingly with their bodies. Of course no woman should be forced to have a baby. No person should be forced to have a baby. The responsibilities that come with having a baby are life-long and life-changing. Although the physical wonders and demands of pregnancy cannot be shared, the responsibilities that come with it can and should be shared. One of the most distressing implications I see in many pro-choice arguments is that pregnancy is the responsibility of the woman alone. In the sense I have outlined above, I am definitely pro-choice.

In order to talk about a right to life, as enshrined in Article 3 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, it is crucial to first think about when life actually begins. Up to this point, I have carefully talked about pregnancy as being a process of growing a new human body inside a woman’s reproductive organs. Is that body alive? Although this question is crucial, it is not necessarily straightforward to answer. As a starting point, I hope that most readers would agree that the right to life certainly applies from the moment of birth until the moment of death. This is despite the fact that we are constantly changing throughout our lives. Although we may stop growing physically after 15-20 years, we never stop changing physically. In other areas, such as knowledge, wisdom and love that process of growth will hopefully continue right through life. A new-born baby is completely unable to survive independently and interacts with the world only on the instinctive level of reflex. Nevertheless, it is alive and has a right to life. Crimes of abuse and neglect of babies horrify us at a very basic, instinctive level. Legal protection of the right to life (as with other basic rights) is especially important for the vulnerable and defenceless – adjectives that certainly describe new-born babies.

Nestled inside the protective womb, attached to an automatic, biological support system, the day before its birth that baby is arguably less vulnerable and better protected than the day after its birth. Is there something about the process of birth which confers life upon it? Perhaps taking its first breath, or cutting the umbilical cord? Although these are hugely significant milestones in the journey of development, I don’t believe they mark the beginning of life. Developmentally speaking, it is ready for birth. It is at a stage at which it could be inside or outside of the womb, depending on the vagaries of the timing of onset of labour. Losing a baby in late pregnancy is devastating. We would expect the parents and wider family to mourn such a tragedy. Mourning is something we do when we lose a life, not when we lose an object.

Under UK law, there is a statutory offence of child destruction:

“…any person who, with intent to destroy the life of a child capable of being born alive, by any wilful act causes a child to die before it has an existence independent of its mother, shall be guilty of felony, to wit, of child destruction, and shall be liable on conviction thereof on indictment to penal servitude for life.”

This instrument is not widely used, but it has been used over the years to convict people for deliberately injuring pregnant women in such a way as to kill an unborn child. (To obtain a conviction, it must be proved that the defendant was not acting in good faith to save the life of the mother.) The threshold of determining whether a child is capable of being born alive was originally set at 28 weeks gestation, but later reduced to 24 weeks. This concept of viability of the unborn child is another moment at which one could consider that life begins. The trouble is that viability can only truthfully be determined after the event. In reality, there is no cut-off such as the law seeks to apply. The chances of survival increase with gestational age, but also depend on other factors not the least of which is the level of medical support available. And yet, whether or not something is alive cannot depend on the advancement or availability of medical science. Either an unborn child of 26 week gestation is alive or it isn’t, regardless of whether it is in 1918 or 2018 or whether it is in Germany or South Sudan.

Another option is to consider that life begins when the heart starts beating (usually at a gestational age of around 6 weeks). This is a tempting suggestion because it is something that can be detected reasonably accurately with modern ultrasound scans and it is one of the most important milestones in a pregnancy. However, it starts spontaneously, with no intervention from outside. It was an event that was programmed into the embryo – the embryo that has been changing and developing by itself, within the miraculous protective environment of a woman’s body, since the moment of conception. If that isn’t life, what is? And so, however I think about it, I can only conclude that life begins at conception. If sperm and egg do not come together then nothing happens. If they do, then a process has started that will, unless it malfunctions or it is interfered with, result in a new person. I am definitely pro-life, from the moment of conception.

How, then, do I resolve the clash between the woman’s right to choose and the unborn child’s right to life? Actually, I don’t think that such a clash is the real problem. The real problem lies in the fact that the world has chosen to tell a lie about contraception: that it gives us the power to completely separate sexual intercourse from pregnancy. It does, of course, hugely increase the level of control we have, but it does not give us total control. No method is 100% effective and we cannot control when the failures might occur. When we have sexual intercourse, therefore, there is always the possibility, however remote, of it resulting in pregnancy. On the other hand, when pregnancy is the desired outcome, stopping contraceptive use by no means guarantees that it will occur. Total control of such matters remains beyond us. The message that men and women choose whether to open themselves up to the possibility of pregnancy when they decide to have sexual intercourse is, I fear, not one that the world wants to hear. This doesn’t stop the message from being true. It is choice that should be made by both partners and for which both should be responsible. A pro-life message cannot, therefore exist in a silo. It has to exist alongside honest teaching about the responsibilities inherent in the choices we make regarding sex.

There are, sadly, occasions when we do have to resolve a conflict of rights. In the case of rape, a woman has already had her right to choose what happens to her body violated. If she becomes pregnant as a result then that is clearly a choice that has also been taken away from her. How she resolves the traumatic situation she finds herself in has to be her choice. Hopefully it is not a choice that she has to make alone, but in the end I believe it has to be her choice. I would still view an abortion as ending the life of the unborn child, but also recognise that the trauma may well be so severe that she feels unable to continue to carry the baby. If people were to clamour for someone to be held accountable for the death, I would be of the opinion that accountability lies with the rapist. Rape is a vile crime.

Another possible conflict of rights is between the right to life of a woman and the right to life of her unborn child. Well documented cases of this sort are often cited in abortion debates. Although rare, such events will occur and we need to be prepared to resolve them sensitively and compassionately. Again, hopefully the woman will not face that burden alone. Both the Eighth Amendment of the Constitution of the Republic of Ireland and the UK offence of Child Destruction recognise that such situations will occur. There are, of course tragic cases where both lives end up being lost, sometimes as a result of failure to correctly balance the competing rights. In other jurisdictions, legislation fails to address the reality of such conflicts at all, either in wording or implementation. Such stories are shocking and show us that some change is needed. However, the leap of logic that enables this particular correspondent to claim that such cases thereby prove that all abortion laws are both anti-women and anti-life escapes me. That is well below the standards I expect of The Observer.

Returning to the Republic of Ireland’s referendum, is abortion just a matter of personal morality that therefore requires constitutional change to allow choice? Although I live in a country that does not go in for a written constitution, I would agree with Ailbhe Smyth, leader of the Coalition to Repeal the Eighth Amendment, when she told the Guardian “The constitution should be the place for the values and aspirations of a society, not a place where you deal with the complexities and messiness of everyday life. That’s a matter for legislation.” However, when society regards matters of life and death as being part of the messiness of everyday life, I find myself calling into question the values and aspirations of that society. I believe the Irish constitution has currently got it right in recognising both the right to life of the mother and of the unborn child. Making this work in practice requires honesty about sex, honesty about life and honesty about abortion. Rather than staying in echo chambers, refusing to even hear – let alone acknowledge – the arguments of the other side, couldn’t people come together to have a rational conversation about how to find a better way to uphold a woman’s undeniable right to choose what happens to her body than terminating the life of an unborn child?

As I draw this post to an end, I find myself enveloped by an unexpected sense of calm. It is unexpected because, as well as being a divisive issue, abortion is an emotive issue. Generally, the emotions it provokes in me are anger and sadness. And yet, although the world seems to be moving inexorably in a direction with which I disagree (which usually strengthens these powerful emotions), I find myself, to borrow the title of a book I have recently read, surprised by hope: a hope that gives me the courage to keep on making the argument. I believe that there will come a time when future generations will look back on us in bemused horror that we could be so blinded by our pursuit of individual pleasure and individual rights as to treat the life of unborn children in such a disdainful manner (much as I hope the majority of people now look back in bemused horror on the slave trade). This change will come when someone of the stature and courage of Wilberforce stands up to call out abortion for what it is and declares, to borrow his words, “You may choose to look the other way but you can never say again that you did not know.”

Very well thought out – quite a pioneering piece!

LikeLike

[…] my wife and I had decided to spend our wedding anniversary bearing witness to our belief in the right to life from conception and our grave concerns about assisted suicide by joining the March for Life. After a gentle amble […]

LikeLike